Introduction: A Feast of Serendib

Introduction: A Feast of Serendib

The first time I started writing a Sri Lankan cookbook, A Taste of Serendib, it was meant to simply be a Christmas present for my mother—writing down some of her recipes. The book offered a few recipes in each section, and featured sketches that a friend drew, illustrating me and my mother cooking, including a few choice quotes of my mother scolding me in the kitchen: “ You cannot read and stir at the same time!”

It quickly spiraled into a book, but the focus was still simple—what little I knew of her recipes. It was designed to be accessible to college students, like the one I was at the time. I was an immigrant who had come to America very young, had grown up eating rice and curry every night, but had only a tenuous connection to the food culture of the homeland.

My mother had had to make many adaptations when she came to America in 1973. She used ketchup instead of tomatoes, for example, because she didn’t have access to coconut milk, and cow’s milk didn’t have sufficient sweetness. (Ketchup also sped along the sauce-making process, since it’s basically a cooked down mixture of tomatoes, vinegar, sugar, and salt.) My mother’s recipes had already changed in America, and as I made them myself, they changed further, adapting to my tastes. When I gave my mother the finished book, she was pleased, but also immediately started pointing out where I’d gotten things wrong. I threatened to do a second edition of the book, with “ Amma’s corrections” all through it in red. I still think that would have been a good book, but she didn’t go for it.

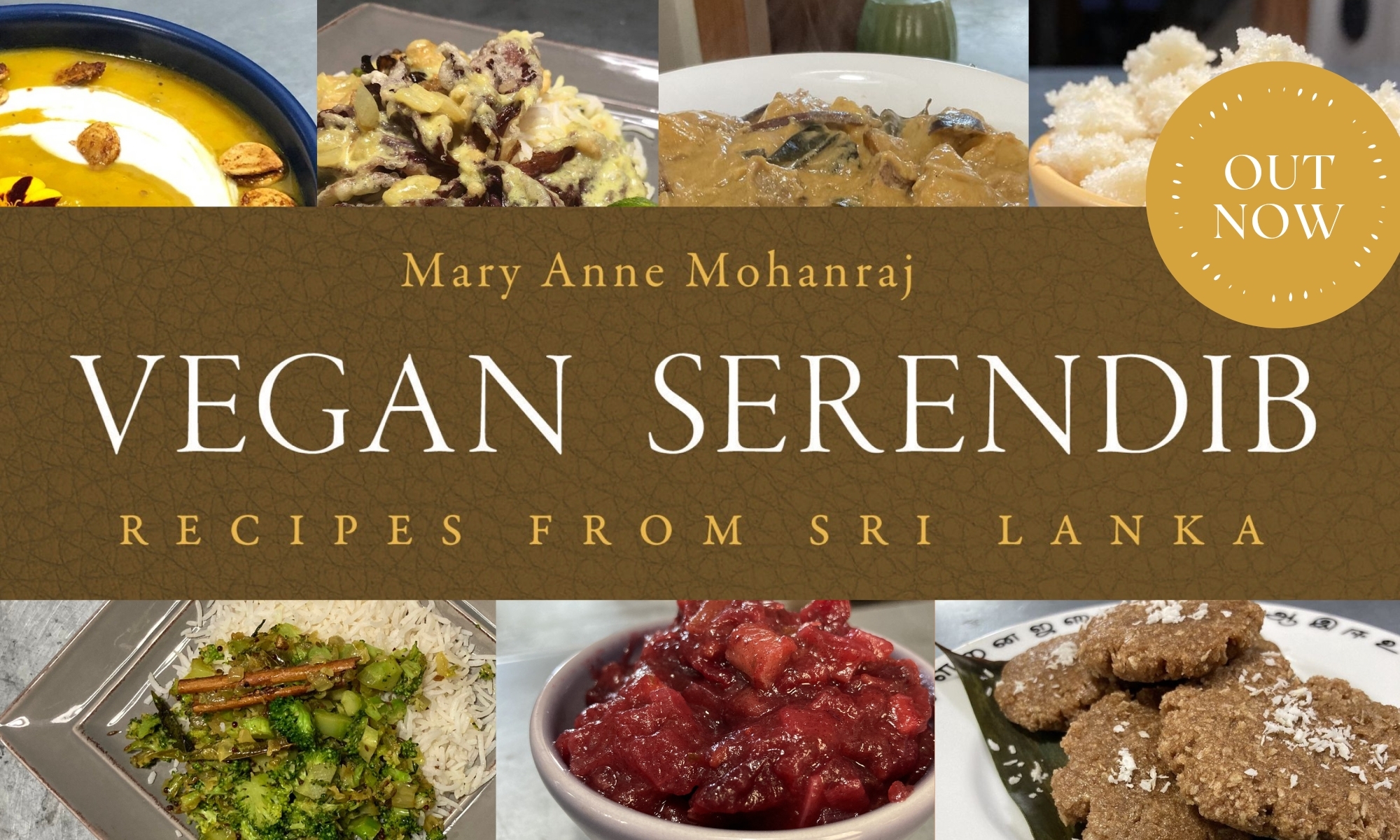

So the book stayed as it was for many years. It could have been left there. But instead, more than a decade later, I started working on a new cookbook, A Feast of Serendib.

My husband, Kevin, and I were talking recently about how I choose which projects to work on. There’s often a pressure to spend my time and energy on more commercial projects, the ones that have the best odds of a good payout. This new cookbook should sell some copies; hopefully, it’ll sell lots of copies. But it’s hardly the most commercial project I could work on, and making the recipes, some of them over and over again, trying to get them right, has been exceedingly time-consuming. If it were just about the money, this cookbook would make no sense at all.

But it’s rarely just about the money. Over the years since I did the first cookbook, I have added more and more Sri Lankan recipes to my repertoire. My cookbook shelf has been overtaken by Sri Lankan cookbooks: from classics like the Ceylon Daily News Cookbook; to conflict-related books like the beautiful and heartbreaking Handmade; to fancy coffee table books full of glorious photos like The Food of Sri Lanka; to what is still my favorite, Charmaine Solomon’s Complete Asian Cookbook—her Sri Lankan recipes taste like my mother’s, like home.

I enjoy cooking dishes from other cuisines. Ethiopian is one of my favorites, and there are days when I crave sushi. Pizza is a family standby, and my children are built in large part out of mac-and-cheese. But I come back to Sri Lankan food—I cook it at least once or twice, most weeks. These days, I go online and read a dozen different recipes for a dish before I even start making it. I interrogate my Sri Lankan friends (both diasporan and homelander) about their recipes. I want to know how these dishes were typically made, in the villages, for generations and generations back. What should the balance of upu-puli (salty-sour) be? How thick do we want the finished gravy?

If I can’t get a certain leafy green considered key to traditional cookery, I feel such frustration. But I try to accept the truth, that I will likely never cook exactly how homeland Sri Lankans would. My adaptations of my mother’s adaptations are still tasty.

My husband is white American, for enough generations that he’s not sure exactly where all his ancestors came from. Once, when Kevin and I were talking about naming our first child, about whether to give her a Tamil name, he asked whether we wouldn’t be better off if we didn’t cling so hard to ethnic, racial, nationalist traditions. Divisions. In some ways, I think he’s right. Sri Lanka was riven by ethnic conflict for decades, and the country and its people are still dealing with the aftermath —it would be worth giving up much, if you could thereby make the conflicts end.

But this is who we are; this is what it is to be human. We are composed of our mother’s hand with a salt shaker, the squeeze of fresh lime at the end of the dish. For those of us who are attenuated from the food of our grandparents and great-grandparents, learning how to cook this food, in its many iterations, can feel like filling a hole in your heart. We named our daughter, Kaviarasi, in the end, a very old Tamil name, which means ‘queen of poetry.’ Diasporic friends of my parents sent us thank you notes, for giving her such a classic Tamil name, for keeping the traditions alive.

I choose this. I choose to put time and energy into learning this food, into serving it to my mixed-race children, with the hopes that they will grow to love it too. Kavi comes into the kitchen to ask excitedly, “ Oh, are you making the yellow chicken?” That’s the Sri Lankan ginger-garlic chicken that she likes better than any other chicken, and when she asks for it, my heart skips a beat.

We come together with other Sri Lankans—homelander and diaspora, Sinhalese and Tamil, Buddhist and Hindu and Christian and Muslim—over delicious shared meals. Sri Lanka has been a multi-ethnic society for over two thousand years, with neighbors of different ethnicities, languages, religions, living side by side. We try to teach our children to be welcoming to all, to share our unique cultural traditions. That is part of what it means to be Sri Lankan, what it has always meant.

Can we choose the good parts of our culture to cherish, and leave the darker aspects behind? I hope so. I hope food can help provide a pathway there. Come together at our table, sharing milk rice and pol sambol, paruppu and crab curry. Linger over the chai—just one more cup. Eat, drink, and share joy.

As for me, I make no claim to authenticity—there are many more authentic Sri Lankan cookbooks, painstakingly researched. But if there was a thin line drawn with that first cookbook, connecting me to the food of my ancestors, then the last few years of researching and adding recipe after recipe to this cookbook have thickened and strengthened the thread of connection, into a sturdy rope. One that you might use when lost, to find your way home.

I’ve come to appreciate the long history, the gathered wisdom of a thousand thousand cooks, who have know that with the perfection of hoppers at breakfast, all you need is a little fresh coconut sambol to accompany it, with perhaps an egg cracked into the center to steam. The more I cook these recipes, the more I grow to love this food.

I hope other readers of this cookbook will feel the same, and will love Sri Lanka, its food, and most of all, its people, along with me.

– March 2019