I’ve been thinking a lot about high / low culture lately, about who gets to publish where, and about genre distinctions: wildly anxiety-provoking, quietly infuriating.

I was just reading Eat Joy, a new collection of food essays from noted writers, from Edwidge Danticat to Alexander Chee to Amitava Kumar to Chimananda Ngozi Adichie to Carmen Machado. I would have LOVED to be in this book. If only I’d seen the call, or been on the editors’ radar. I would have loved to at least submit something.

Here’s a bit from the first essay, “Leaves,” by Diana Abu Jaber:

“Reportedly, the Israelis have outlawed the picking of herbs like za’atar and thyme, contending that such plants are endangered, and encouraging its cultivation in gardens instead. But wild za’atar is said to be the miraculous herb that fed the Palestinians, an ingredient at the heart of their food and identity for ages. There are no substitutes.”

It’s a lovely piece, and wouldn’t be out of place in The New Yorker, Creative Nonfiction, etc. But it could also have been published easily in a food magazine like Gourmet or Bon Appetit. How does a writer decide where to send such a piece? How should they make those decisions? Is a piece not ‘serious’ if it appears in a big commercial venue? How about if it’s written with the intent that it be inviting and easy to read? Must serious literature be ‘hard?’

I struggle these days with the question of whether the books I’m doing, the ones I’m interested in, are ‘serious’ enough for my academic department. This is almost all coming from me, not them, and yet. And yet.

Bodies in Motion, my 2005 immigrant novel-in-stories, was so clearly literary fiction…

— I have to sidebar here to note that I resist that term, literary fiction. I’d reframe that genre as mainstream fiction or realist fiction, with ‘literary’ as a modifier that you could also apply to some works of SF/F (Le Guin, Delany, etc.) or mystery (Lori Rader-Day’s work, etc). I was just listening to Gary Wolfe on his Coode Street podcast; the latest episode has a long discussion of this struggle within the SF genre, to be seen as literary, as serious, as worthy of respect.

They implied a distinction between a large commercial audience, and lasting reputation. Have more people read George R.R. Martin’s _Song of Ice and Fire_ than James Joyce’s _Ulysses_? Perhaps. Will George’s writing be remembered, canonized, in a hundred years? And what about writers like Gene Wolfe — writing ‘hard,’ dense fiction like Joyce, but without the imprimatur of the literary establishment to bring his work into college classrooms and Norton anthologies? How much longer will Wolfe be read, and by how many?

I’d love to throw many of these genre distinctions away. They’re not actually useful, except perhaps to marketers who are trying to sell books to a dedicated audience that is particularly interested in that subset of fiction. —

…but anyway. I wrote Bodies in Motion during a doctoral creative writing program, where I was spending masses of time thinking about narrative structure, about language and form, where I was immersing myself in other comparable fiction. I brought to that book all the attention to details of craft and prose that I was capable of.

That’s probably what I’d define as ‘literary,’ by the way, if I had to come up with a definition — writing that aims towards art, privileging the artistic goal over the needs of commercial fiction, which may be looking more towards fast pacing, lots of dialogue, an ease of reading.

But as soon as I say that, I want to hesitate and caveat and take it all back. Because of course there is literary fiction that is fast paced, with lots of dialogue, that’s easy to read. And I certainly know many commercial fiction writers who pay intense attention to details of craft. One thing I absolutely want to avoid is any automatic mapping of ‘literary’ onto ‘good’ and ‘commercial’ onto ‘bad.’ That frankly strikes me as lazy, elitist, and worst of all, inaccurate.

Which is not to say that I don’t think there’s such a thing as ‘bad’ fiction — unlike a few of my writer/editor friends, I’m willing to say that there is. But what constitutes ‘badness’ is almost completely orthogonal to what constitutes ‘literary.’ Badness is a separate essay altogether.

[Dammit, the whole literary fiction distinction was supposed to be a sidebar, but I keep coming back to it, so perhaps it’s really the meat of this meditation, but never mind. Onwards.]

Bodies in Motion had all the trappings of literary fiction. It was reviewed by major outlets, and taken seriously by them. I won’t make you wade through all the reviews, but here’s a bit from one of my favorites. Reviewer Kim Hedges at the SF Chronicle really GOT what I was trying to do with the book on an artistic level, and I felt so grateful for her careful reading.

“Mohanraj’s writing style is spare and piercing, and she exercises a sophisticated economy of language. Indeed, words left unspoken are not only a technique of Mohanraj’s but a defining characteristic of the lives of her characters as well….It thus becomes noteworthy that a collection containing so many figuratively paralyzed individuals is titled “Bodies in Motion.” Much of this collection is about juxtapositions: characters finding ways of movement in situations that seem hopelessly static. People must compromise, finding pockets of richness amid deprivation of truth, sex, love and self-expression….In spite of disappointments and foiled expectations, Mohanraj’s characters persevere; even when language fails, their bodies remain in motion.”

It sounds quite literary, doesn’t it? Such a privilege and kindness to have your writing looked at with such care, such willingness to see its worth, to draw out its best features. A writer’s dream, the sort of review that might lead others to read a book with similar care and openness to its best qualities.

Yet with even that perceptive review, Hedges opened her review by framing the book as ‘not erotica.’ “Sensuality is undeniably important in these 20 consummately elegant, inspired stories, but this is more than frothy erotica.” We cannot take seriously something that might be read as genre, apparently.

I don’t blame Hedges for that line — she was trying to defuse potential criticism, to make it more possible that others would take my book seriously, despite the racy half-dressed woman in a red sari on the cover. (Oh, that cover. That’s another essay.) But her line does reflect the assumptions of the literary culture of the time. Erotica is by definition frothy? As SF is by definition the province of boy’s adventure stories with rocket ships, and romance is by definition mere women’s escapism?

I know, I know. Much of the literary world has, actually, moved on from these divisions, thankfully, in the last decade. But I’ve been writing and publishing for 25 years, and the same defensiveness that I saw in the Le Guin documentary, the same anxiety of ‘is the work serious enough?’ is still embedded in me. I’ve been carrying the weight of it, letting it bow me down. (My mother says that I’m developing a hump.) No doubt that weight is aggravated because my day job is in an academic department.

If I don’t write ‘literary’ fiction that is taken seriously, winning the right awards, getting the right grants, am I still doing the job they hired me for? I used to be solidly in that literary sphere in 2005, but as my interests have shifted over the last decade, I often feel that I’m drifting further and further away from what my department might consider ‘serious’, worthy of note (and worthy of merit pay increases).

Relatedly, how many of those grants, awards, reviews are contingent on networking, on knowing the right people? Not because the game is consciously rigged, as the Sad Puppies thought, but because it is human nature to rely on trusted sources, esp. in this age when we have inputs coming at us from every direction, and we can’t possibly read everything we should.

(After all, Hedges only saw my book, and was ABLE to review it, because HarperCollins invested the money in a beautiful slip jacketed hardcover, with the ragged as-if-hand-cut pages that signal ‘this is serious’, and sent it to her, with appropriately glowing promo material. If you don’t have the money or reputation to lift your work out of the sea, what’s an indie author or small press to do?)

Readers rely on reviewers in our sub-genres; we rely on our friends’ recommendations. Word of mouth is still the most powerful force in publishing, and in some ways that’s good, but it also means that it’s SO EASY for genre-blurring or otherwise marginalized work (and writers) to be missed entirely.

My ADHD-influenced genre switching (but I do genuinely love all these genres, and try my damnedest to write well in all of them) is the despair of my agent. How can he help me build a career and a reputation, if I won’t just stick to one thing?

Would I be a better SF writer, if I had spent 25 years doing only one that? Almost certainly. Would I be a better writer overall? I don’t think so? Would I be happier? I have no idea.

I visited a colleague’s class last week, and brought along some books to show the students.

Here’s a half-dozen books, the decade of erotica. Here’s the serious literary book, translated into six languages, with a big advance and glowing reviews. Here’s the small SF novella I wrote and was going to self-publish until a small press picked it up. It’s also full of sex and a finalist for all the queer awards, but not really on most folks’ radar otherwise, in either SF or mainstream fiction.

Here’s the cancer / garden romance from the same small press. They were kind enough to publish it, but didn’t manage to find its market, so perhaps a hundred copies have sold. Poor Perennial — I rather failed that little romance. It’s full of pain and poetry, an experimental juxtaposition of serious poetry / memoir and deliberately ‘frothy’ romance; I would call it ‘literary’ in that experimental writing sense, but I’m not even sure I thought to give my department a copy. I certainly didn’t try to get it into the hands of literary fiction reviewers. It’s just a romance, after all. It’s not serious.

I’m on a panel on Sunday about romance, which presumably they added me to because my bio says I wrote a romance. I’m honestly more than a little embarrassed that that’s where I chose to spend my time and attention for much of a writing year, even though I shouldn’t be. Jane Austen wrote romances, after all. So did Shakespeare. And yet the genre as a whole is appallingly devalued — because it’s written by women? Because there *is* a large percentage written to a somewhat shlocky formula? See also Sturgeon’s Law.

(Sturgeon is, btw, a gorgeously stylish and brilliantly gender-and-sexuality-exploring SF writer of the 50s, whose work should be mandatory reading in college classrooms now. It isn’t.)

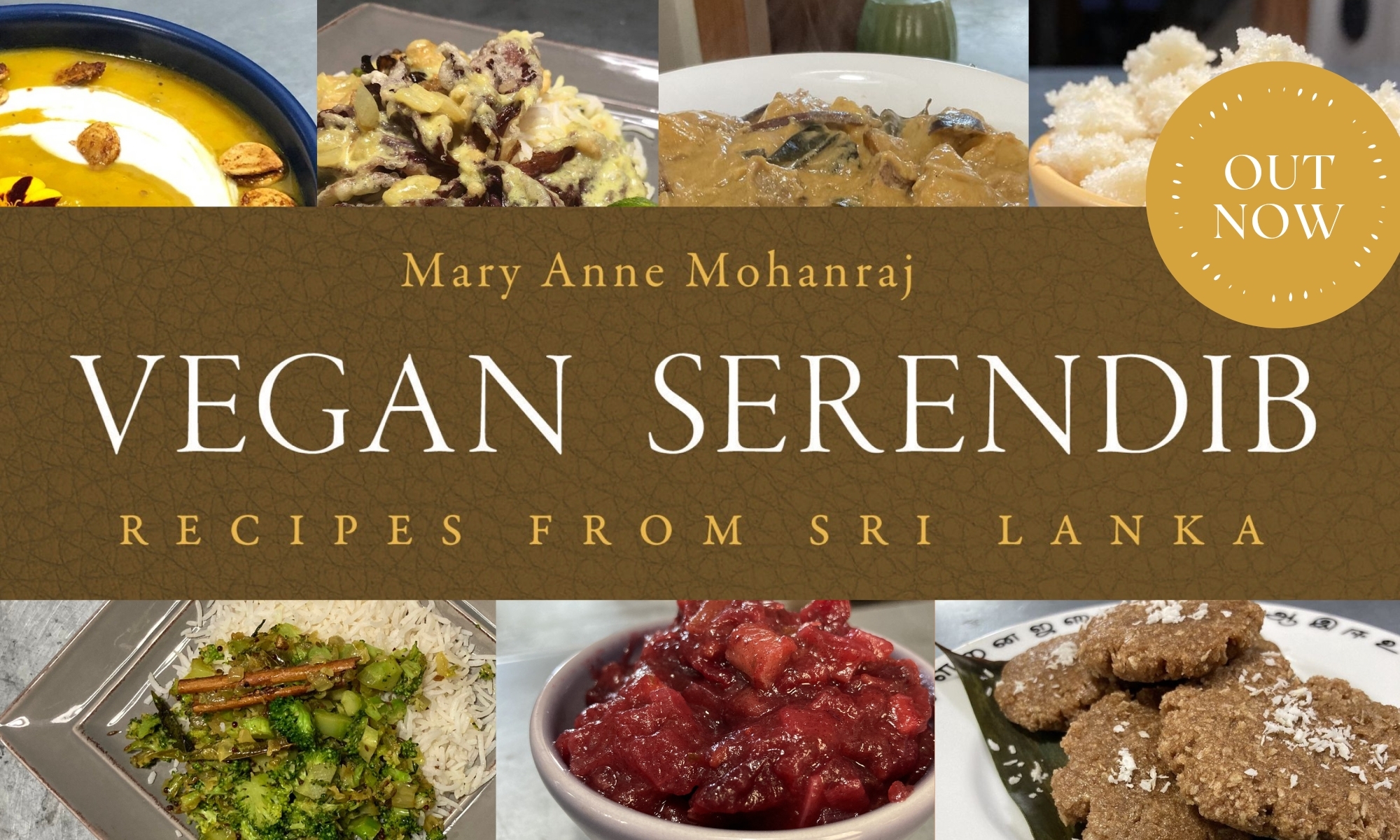

And now here’s a cookbook. They’re all different genres, these books, but in some ways, I feel like they’re all the same — in each one, what you get is me, my way of thinking and approaching the world, my way of seeing other people and communities, for better or worse. They’re in conversation with each other, and if I’m ever lucky enough to have an academic study my work seriously, they’re going to have to read it all to do it right. (Too intimdating a task, I’m afraid. Ah well.)

The books are in conversation with all the posts to my blog & FB wall too, including this one. I might argue that blogging is actually my most ‘serious’ and ‘literary’ project to date (and certainly my most widely read and influential.)

Yet there is no place on the university forms to cite FB posts as evidence of publication and merit pay increase worthiness. [That’s a SF reference, btw, ‘there is no place on the forms,’ to a Bujold novel which also isn’t taken seriously by the literary establishment. _Komarr_ is one of my all time favorite books, and I have read it to tatters. My department colleagues are brilliant and immensely well read, and yet probably haven’t heard of it.]

So here I am now, switching genres yet again — that was abrupt! — with a cookbook. On a plane, heading to a conference, but I’m not going to a food event. (Sorry, Pem, my poor publicist.)

I’m going to the World Fantasy Convention, where I will interview SFF writers and editors for my SFF arts foundation. Since getting on the plane, I’ve just directly queried two editors I know, whose work I respect, about the SF novel I finished this past summer, to see if either would be interested in looking at it. I’ve also written to a grad school classmate to see if she’d be interested in editing a book about food and the environment with me. Switch. Switch. Switch. Switch.

When I finish this post, I’ll turn to drafting food essays to pitch to big commercial food magazines, but they could as easily sit in a ‘literary’ magazine. I will try to place them in both, with perhaps minor adjustments of style. They’ll reach different audiences. The dream, of course, is that the book breaks out, that it gains enough visibility that ALL the different sets of readers who might love it become aware of it.

Yet however all that goes, whether A Feast of Serendib sinks or swims gloriously forth, the real challenge is to stay true to my writing interests. To write what I want to write, in this small space I have on this earth. Pushing away thoughts of fame and fortune, pushing away anxieties on all fronts.

Or if those thoughts come bobbing up too intensely, then surface them, acknowledge them. Like this. And then, hopefully, put them aside, and go back to the work.

“I have already settled it for myself, so flattery and criticism go down the same drain and I am quite free.” — Georgia O’Keefe

I’m not free yet. Working on it.